China’s ‘Long March’ to escape global risks

Beijing is seeking to reduce the threat of diplomatic isolation as it moves to become a major US rival

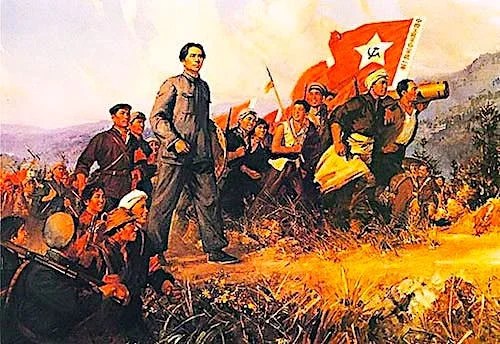

In 1934, Mao Zedong’s embattled guerrilla forces began what was to prove an epic military withdrawal from southern China to a stronghold in the north of the country.

This became known as the Long March. It enabled the Communists to break out of so-called “encirclement campaigns” to fight another day against Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists.

In Chinese Communist Party history, there is hardly a more indelible moment. It is certain to have been imprinted on the consciousness of Xi Jinping by his father Xi Zhongxun, a Mao-era military commissar and later a vice-premier.

Fast forward to 2021, and there have been signs in recent weeks of China seeking to reduce the risk of geopolitical isolation in its own diplomatic “long march” – to become the pre-eminent power in the Asia-Pacific and global rival to the US.

Sometimes forgotten in the ideological debate in the West about Beijing’s motivations under Xi is that Chinese leaders are pragmatists conditioned by ruthless internal Communist Party politics.

So a reasonable question now is whether Xi and his advisers have understood that the risks of overreach in China’s interactions with the outside world outweigh the benefits.

In other words, where lies the zero-sum game?

Chinese statecraft

One aspect of Chinese statecraft to keep in mind is that Beijing will seek to get away with whatever it can.

Viewed from behind the vermilion walls of Zhongnanhai, Beijing’s leadership compound, American-led efforts to “contain” China will have taken on some of the characteristics of an encirclement campaign.

Beijing’s reaction has been relatively muted, by its standards, to the recent announcement of the AUKUS alignment between Australia, the UK and the US as a China containment front. But Chinese leaders will nonetheless view this as part of a latter-day encirclement campaign.

Likewise, the elevation of the Quad grouping of the US, Japan, India and Australia would be seen in Beijing as a further example of US-led China containment architecture.

Apart from the usual bluster in Chinese Communist Party mouthpieces like the Global Times, what has been Beijing’s response to all this?

The short answer is that it has been engaging in some creative diplomacy to lessen the risks of geopolitical isolation.

This has involved:

- the engagement at presidential level between Xi and Joe Biden with promise of a virtual summit by the end of the year

- the makings of a charm offensive in Beijing’s dealings with the European Union

- an application to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) on top of joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)

- a “hostage exchange” enabling the release from detention of the daughter of one of China’s most powerful businessmen

- an announcement that China would stop funding coal-fired power stations abroad. This comes ahead of the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), where it is expected to play a leading role.

In Australian policymaking circles, dominated by a national security establishment wedded to seeing China as a threat, the above developments might be weighed.

In the case of Xi and Biden, the issue is not so much whether there is a thaw in Sino-US relations after the wrenching Donald Trump era. It is more about whether the world’s dominant powers can establish a relationship that enables reasonable dialogue and even cooperation.

In the Xi-Biden phone call on September 9, the two agreed there was too little communication between Beijing and Washington. It was followed this month by a six-hour in-person meeting in Zurich between National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan and his Chinese counterpart Yang Jiechi.

The upshot is that Xi and Biden will meet “virtually” within weeks.

Positive development

Significantly, Biden in his conversation with Xi reiterated America’s commitment to the spirit of the Shanghai communique that enabled the issue of Taiwan to be set aside.

This should be regarded as a positive development.

In Beijing’s dealings with the European Union, the several sessions with top European officials conducted in late September by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi are notable.

Wang’s strategic dialogue with Josep Borell, the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, followed discussions with NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg.

These were aimed at clearing the air after strong criticism and censure in Europe of China’s mistreatment of its Uighur minority, and arguments over Taiwan.

In another important development, Xi was due last Friday to speak with European Council President Charles Michel.

On Wednesday of last week, the Chinese leader held a “friendly” phone call with outgoing German Chancellor Angela Merkel. The two discussed preparations for the G20 summit in Rome, climate change issues ahead of COP26 and the European Union’s stalled investment agreement with China.

The latter has been interrupted because of tensions between Beijing and Brussels on the Uighur issue and other stresses.

This flurry of diplomatic activity could not contrast more sharply with the deep freeze in relations between Beijing and Canberra, with high-level contacts at ministerial level suspended.

Perhaps most significant of recent China’s diplomatic maneuvers has been its request to join the CPTPP, which groups 11 Asia-Pacific countries in a trade bloc.

The Obama administration originally conceived of the CPTPP as a means of pressuring China on trade and security issues. Trump’s abandonment of the trade bloc has enabled China to make a bid for membership.

The Australian government has said China could not be considered for membership until it relaxes its punitive trade campaign against Australian exports. Individual members have veto power over new entrants.

In any case, Beijing would have difficulty meeting the trade-liberalization requirements of the CPTPP.

On the other hand, China’s request for membership simultaneously with that of Taiwan renews focus on regional trade agreements in which Beijing is active.

China joined the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) last year and is a principal sponsor of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Diplomatic front

On the diplomatic front, the deal enabling Huawei’s Meng Wanzhou’s return to China from Vancouver in a hostage swap removed a significant irritation in US-China ties.

Finally, China’s announcement it was ending its funding of coal-fired power stations abroad was clearly aimed at window-dressing its patchy performance on climate issues ahead of the G20 summit in Rome and COP26 in Glasgow.

These diplomatic shifts do not necessarily amount to a breakout moment for China in its troubled relationship with the international community.

But it would be a mistake for countries like Australia to assume China will continue to alienate a wider international community if it believes its actions are proving inimical to its own interests.

Tony Walker is a vice-chancellor’s fellow at La Trobe University in Melbourne.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of China Factor.